What Is the Mississippi Delta?

Physical Description

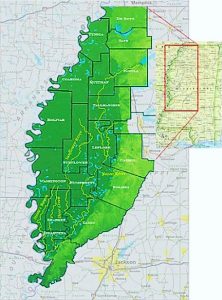

The Delta is approximately 200 miles long and 70 miles wide at its widest point. It is bounded on the north by the Chickasaw Bluffs upon which Memphis, Tennessee is situated, and extends two hundred miles south to Walnut Hills, north of Vicksburg, Mississippi. The eastern boundary is a concave line of loess-capped bluffs, some two hundred feet high, that form a pronounced escarpment between the Yazoo Basin and the hill section of Mississippi to the east. The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta is a basin that narrows

at the northern and southern ends. The northern end of the Basin is 210 feet above sea level, sloping to 90 feet at the southern end (0.0014 in/mile). The Basin slopes eastward from the Mississippi River to the bluff line with an approximate 15 foot drop in elevation (0.00045 in/mile).[3] Putting it another way, the Delta is flat, very flat.

It is a well-known characteristic of human culture and language that people develop a fine-grained, detailed vocabulary around features of their environment that are of importance. Cultures have a vocabulary about food, its creation, preparation, presentation, etc. etc. Likewise, Eskimo have a rich vocabulary about snow. Farmers in the Mississippi Delta have a vocabulary about the land. In the extreme, land is sand or clay. Likewise, is it good land or poor? What are the characteristics of the soil that determine quality? Whether soil holds water or not depends, to a considerable extent of how much sand is in it. If sand is replaced by clay soils, the soil will hold water. How these to characteristics are represented in any area determines its suitability for farming. Soils in the Delta are characterized as “buckshot”, “sand-blow”, “rice land”, “cotton dirt”, “precision leveled” or “gumbo.” All are descriptive terms, which tend to describe both the relative clay/sand content of Delta soil and its elevation.

All the dirt in the Delta was once a brown turbid liquid created from the Mississippi River drainage area, about 1.2 million square miles including all or parts of 32 states and two Canadian provinces, or about 40% of the continental United States. Since floodwater travels in a non-uniform, turbulent manner, water velocity is higher in some areas than others. Because sand particles are much larger on a microscopic level than clay particles, it takes greater water velocity to keep sand suspended than it does clay. Hence sandy soil is most often found near old waterways when floodwaters recede. As flood waters recede, they slow down causing heavy sand particles to drop out of suspension, usually very close to the fastest water in the center of the waterway. Each flood cycle repeats this process until eventually a waterway creates its own natural levee out of sand and silt near the edge of the waterway channel.

Eventually, enough sand and silt accumulate that the waterway will choke itself out, causing the waterway to find a new course. Land left behind in the process is often called “sandy land” or cotton land. Its high sand content and non-cohesive nature allow water and air to infiltrate readily, traits desirable for cotton cultivation. Interestingly, this natural levee-building phenomenon results in the highest land in the Delta is usually found near the Mississippi River. Throughout history the Mississippi River has breached natural or man-made levees and those breaches are sites where water velocity can be extremely high. High velocity water carries very large particles, breach sites often exhibit a soil type called “crevasse” which consists of coarse sand known in the local parlance as a “sand blow”.

On the other hand, since clay is much lighter than sand, it stays in suspension much longer. Clay predominates in areas where water has stood for long periods of time, and these are usually low places. “Bottoms” are usually clay soil, and they are suitable for rice production because they hold water well. Clay soils can be very homogeneous and cohesive, meaning that the tiny particles stick together tightly therefore conducive to land leveling. Water does not penetrate well, which is why a rice paddy does not lose its water as does sandier soil. However, if a clay soil is not drained well on the surface, plants can become waterlogged and produce poorly. Clay is sometimes called “buckshot” because when it dries it cracks and forms little particles like BB’s. When wet, the clay soil in the Delta assumes a consistency of gumbo.

Typically, clay soils are found in the lowest parts of the Delta away from the Mississippi River. This is not always true today, since the Mississippi has shifted its course many times over history. Nowadays, the Corps of Engineers is responsible for maintaining the channel in its current location, an effort that is not natural but essential for commerce.

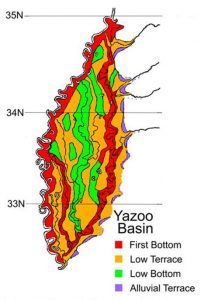

There are differing soil types in the Delta that directly affect the type of agriculture practiced. From top to bottom, they include: the First Bottom soils are the highest in the Basin and are coarse soils not subject to frequent flooding. These are the best drained soils in the Basin and the ones that have been in cultivation the longest. These soils were attractive to early settlers since they are the least likely to flood, drained well, and are easy to cultivate. The next type of soils that were brought under cultivation are the Low Terrace soils. These are soils must be drained but are well-suited to cotton and corn cultivation. The most extensive soils in the Delta are the Low Bottom soils. They are five to ten feet deeper than the other soil types and reach a depth of 40 feet in the southern reaches of the Basin. The soil consists of silty clays and with high organic content and is an extremely fertile soil that can be farmed intensively.

Cultural Description

According to David Cohn “… The Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and extends to Catfish Row in Vicksburg. The Peabody Hotel is to Memphis as the Ritz is to Paris, the Shepheard to Cairo, or the Savoy to London. If you stand near the fountain in the middle of the lobby of the Peabody, where ducks waddle and turtles drowse, ultimately you will see everybody who is anybody in the Delta and many who are on the make.” The Peabody Hotel is synonymous with cotton. Opened in 1869 it quickly became the social and business hub of Memphis and by extension, the Mississippi Delta.

While the original hotel has long been demolished, and the ducks were not introduced to the hotel’s lobby fountain until 1933, it is easy to imagine people gathered near the elevator to witness the traditional daily ritual of the Peabody Duck March. Every day at 11 a.m., they are led by the Duckmaster down the elevator to the Italian travertine marble fountain in the Peabody Grand Lobby. A red carpet is unrolled and the ducks march through crowds of admiring spectators to the tune of John Philip Sousa’s King Cotton March. The ceremony is reversed at 5 p.m., when the ducks retire for the evening to their palace, the “Duck Palace”, on the roof of the hotel.

The Duck March originated in 1933 when Frank Schutt, General Manager of the Peabody, and a friend, Chip Barwick, returned from a weekend duck hunting trip to Arkansas. After a few drinks, they thought it would be funny to place some of their live duck decoys (legal at that time) in the beautiful Peabody fountain. Three small English call ducks (the smallest of all duck breeds, bred originally as decoy ducks) were selected as “guinea pigs,” and the public reaction was enthusiastic.

Soon, five North American Mallard ducks, one drake with his white collar and green head, and four hens with less colorful plumage, replaced the original call ducks. The ducks are raised by a local farmer and a friend of the hotel. Each team lives in the hotel for only three months before being retired from their Peabody duties and returned to the farm to live out the remainder of their days as wild ducks.

In 1940, Bellman Edward Pembroke, a former circus animal trainer, offered to help with delivering the ducks to the fountain each day and taught them the now-famous Peabody Duck March. Mr. Pembroke became the Peabody Duckmaster, serving in that capacity for 50 years until his retirement in 1991. Honorary Duckmasters have included Patrick Swayze, Florence Henderson, Emeril Lagasse, Joan Collins, Molly Ringwald, Chris Matthews, Larry King, and Kevin Bacon. The ducks have appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, Sesame Street, when Bert and Ernie celebrated Rubber Ducky Day, and featured in People magazine as well as the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue. In addition, they were once a question on Jeopardy.

When one hears of the Mississippi Delta the images of cotton fields and plantation mansions come to mind. In reality, there never were the number and nor the opulence of the antebellum homes that are found in and near Natchez. To be sure, there were some impressive homes in the Delta before the Civil War, but those few were located near the Mississippi River or along secondary rivers in the Delta. In general, the Delta in antebellum times was heavily forested and much was seasonally flooded. While it was clear that the land was exceptionally fertile, clearing it was a major task. Most of the homes in the Delta were casualties of the Civil War.

Clearing this dense vegetation for cultivation was a Herculean task for settlers intent on planting cotton and typically took several years to complete. Clearing was primarily an activity best done in the dry seasons. The dense vines and undergrowth were cleared during the first year of cultivation with axes using mules and chains. Oak and cypress were the first trees to be cut and hauled out.

An experienced “full hand” might cut an eighth of an acre a day. Initially, trees were girdled by cutting a wide strip around the circumference of the entire tree making it vulnerable to disease, mold, insect infestation, and dehydration. Girdled trees would die within three years and were cut and burned along with other cleared vegetation at the end of the cotton season. Limbs, vines, and branches would be piled around a tree stump and then burned. Cotton could not be grown until the second season, when mules could plow around the trees and tree stumps when some cotton could be planted.

The beginning of the 20th century witnessed the introduction of gasoline-powered, sled-mounted stump saws pulled by a mule team from stump to stump. The belt driven stump saw could cut the stump off even the surrounding soil, rather than trying to dig it out of the heavy clay soils. By the 1930s farmers were adapting old automobile engines and differentials to stump saws. Since WWII mechanical equipment has been used to clear land in the Delta, but in many cases such equipment was not commercially available and was designed and manufactured by local farmers to meet specific conditions.

Today it is safe to say that virtually any land that can be farmed, is. To put it a bit differently, there is little if any land left in the Delta that could be developed for farming. The Delta was populated and the land cleared for one primary purpose, agriculture. Today that statement is as true as it was 250 years ago. The alluvial plain that is the Delta has been called the most fertile soil in the world, even more so than the Nile River Valley.

Psychological Description

Much has been written about the Delta, its people, its history, its politics, and its art. It has been said that the Delta produced the greatest literary talent to ever come from a definable geographic region in the US. David Cohn, Ellen Douglas, Shelby Foote, Ellen Gilchrist, Willie Morris, Walker Percy, and Elizabeth Spencer all called the Delta home. To be sure all saw something slightly different in the Delta, but all recognized the psychological hold it can have on an individual. The Delta is full of contradictions, and I suppose to some extent, one’s ability to deal with contradictions and ambiguity is a good predictor of how one might react to the Delta.

I am no different from so many others in finding the Delta a delightful and satisfying place to live. David Cohn referred to the Delta as a land of excesses. The landscape seemed to breed in its inhabitants a profound tendency toward excess in many aspects of life. The Mississippi River with its twists and turns brought not only goods and and a variety of people to the Delta, but also showboats and circuses to Delta towns. Without question, the definitive work on the Mississippi Delta is James C. Cobb’s The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity and one that is an indispensable guide to this curious and fascinating place I call home.

It is possible to live in splendid isolation in an urban environment. It is not here in the country. In some ways the Delta is one of the last American frontiers. It is largely undeveloped, with miles and miles of laser straight roads and expanses of fields as flat as a pool table on either side. Dust from the gravel roads is ubiquitous and mosquitos the size of small birds pose a challenge. Some of the conveniences of the city are simply not available. It is nearly an hour round trip to go to the nearest gas station, so running out for a quick anything is challenge, at best. Of course, those challenges are met with compensatory advantages like peace and quiet, deer in the front yard, neighbors who are willing to help at the drop of a hat, and days that are bracketed by spectacular sunrises and sunsets.

Most important, in my opinion, is that life takes on a tempo of nature. Weather dictates when work in the fields is possible, so life becomes a series of days when work from daylight to dark is possible, when work in the fields may be possible, and as well as the dreaded days of a complete washout. This reliance on the weather has given me a completely new understanding of the things over which we have absolutely no control.

The other important lesson that living here has taught me is that living in isolation is not possible. No plastic bubbles here. Given the harsh nature of the environment, people have developed a fundamental appreciation of our social nature. It is not so much about socializing per se, but it is an awareness that everyone needs help at some time. There is a keen awareness of reciprocity and helping others is simply a way of life.