Area Attractions

And Other Points of Interest

When one mentions the Mississippi Delta to most outside the state, they associate it will all the negative social, political, and cultural issues that have confronted the state for most of its history. Agriculture is the economic engine of the state and nowhere is the more evident than in the Delta. For decades, the principal crop was cotton and cotton is not an easy plant to grown, but the return on investment can be greater than almost any other crop. That was certainly true for the 19th and much of the 20th centuries. Everyone knows that cotton is one of the most demanding crops that is grown commercially, and to grow it in the pre-mechanized era, intensive labor was required. Slaves and tenant farmers were the labor force that allowed for cotton cultivation in the Delta. Growing cotton is hard work and successful cotton farmers necessarily required a large, cheap labor force willing or required to work under harsh conditions. Let me be clear, I am in no way condoning slavery, tenant farming, or any type of bonded servitude, but the demand for cotton in the industrial North as well as Europe was the economic engine that propelled the US to its place as a world power. The farmers in the South, while engaging in labor practices that were beyond the pale, simply were meeting an unprecedented demand by markets far beyond the Mason Dixon line.

Such is the environment that gave rise to a uniquely American music genre, the blues. As an art form, the blues has received considerable attention from not only performers, but music historians, scholars, as well as writers and other artists. Rather than recount information that is widely available in print as well as the internet, I refer the reader to the Mississippi Blues Trail website (http://msbluestrail.org) for additional information on the remarkable history of origin of the Mississippi Delta blues.

Here I want to highlight a few places to those interested in the birthplace of the this uniquely American music, as well some sites often overlooked in a tour of the Delta. As I have said, Serene Fox Farm is in the heart of the Delta and with that, the heart of blues country. It goes without saying that in addition to the blues, the history of civil rights in the United States has been written, in part, in the Mississippi Delta. While I do not pretend to present a comprehensive review of notable sites of the civil rights movement, I include some within an easy drive of the farm. A considerable body of American literature can trace its ancestry back to the Delta and it is easy to imagine from sites easily viewed from the roads that crisscross the Delta, the inspiration for many a writer. Given the location of the farm, some of our closest historical points of interest are:

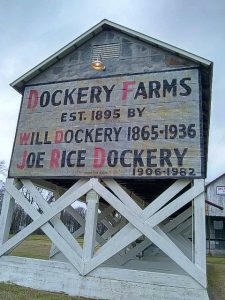

Dockery Farms

In 1895 Will Dockery began purchasing forest and marshland outside of Cleveland, Mississippi, between the Yazoo and the Sunflower Rivers with a $1000 gift from his grandmother. At its zenith, Dockery Farms consisted of 40 square miles of farm and marshland (26,500 acres) replete with wildlife including panthers and wolves, as the ubiquitous mosquitoes.

The Dockery Plantation grew to support over 2,000 workers, and was a quasi-political entity with its own post office, railroad terminal linking the farm to the Mississippi River port at Rosedale, general store (commissary), sawmill, foundry, two schools, doctor, telegraph office, cemetery, picnic ground, and two churches (one Methodist and one Baptist). It also issued its own money in the form of tokens as well as script that was honored on the farm at the commissary as well as in local stores. In addition to a number of cabins and shacks, workers’ quarters also included boardinghouses, where they lived, socialized and played music, particularly guitars, introduced to the area by Mexican workers in the 1890s.

On the northern side of the plantation, far away from the main residence were a number of ramshackled cabins and broken down boxcars that served as shelter for some of residents not interested in agricultural endeavors. It was here that the earliest bluesmen congregated including at various times – Henry Sloan, Charley Patton, Son House, and Robert Johnson to name few. Will Dockery was known for his “fairness” to his employees and tenant farmers, given the state of affairs in the Mississippi Delta in the early 20th century. Today such a view might not be so widely held. Dockery is reported not to have taken any personal interest in his workers’ music. He neither smoked or drank and prohibited any jukes on the plantation, but was tolerant of the artistic expression of his famous residents.

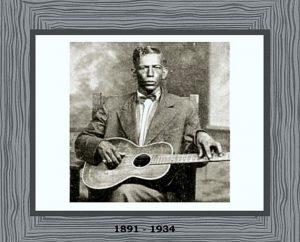

Charlie Patton and his family are believed to have moved to Dockery Plantation around 1900, where he was mentored by an older musician, Henry Sloan who worked on the farm. In turn, Patton became the central figure of a group of blues musicians including Willie Brown, Tommy Johnson, and Eddie “Son” House, who played in towns and jukes near the plantation. By 1920 the physical location of the Dockery Plantation made it a gathering spot for informal musical entertainment. By the mid-1920s, the group widened to include a younger generation of musicians, including Robert Johnson, Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett, Roebuck “Pops” Staples, and David “Honeyboy” Edwards. Some of these were itinerant workers, while others lived more permanently on the farms.

Dockery Farms is approximately 8 miles ATCF NNE from the farm on Mississippi Highway 8 between Cleveland and Ruleville.

Crossroads

The Yazoo-Mississippi delta is a flat, rather featureless alluvial flood plain largely devoid of landmarks. A crossroads is a local landmark and is an easily identified feature of the landscape since it is the intersection of two roads. Not only are crossroads used as geographical landmarks, they are also the best spot to catch a ride if you are a hitchhiker. Robert Johnson’s Cross Road Blues is a singularly important blues song, not only for its lyrics, but the rich retinue of stories it has spawned. In the simplest reading, Johnson describes his grief at being unable to catch a ride at an intersection before the sun sets. The song opens with the protagonist kneeling at a crossroads to ask God’s mercy, while the second section tells of his failed attempts to hitch a ride. In the third and fourth sections, the protagonist expresses apprehension at being stranded as darkness approaches and asks that his friend Willie Brown be advised that “I’m sinkin’ down”. Interestingly, Willie Brown is another Delta blues musician that accompanied Johnson, House, and others on various recordings. It is likely that Cross Road Blues has been covered by more artists than any other blues song.

Robert Johnson was born in Hazlehurst in 1911, but moved at a young age to the Abbay and Leatherman Plantation near Robinsonville. Early in his career he played the harmonica, and was a mediocre guitarist at best. As a teenager he was often seen at the jukes and he stayed in the Delta until his late teens. Interestingly, Johnson left the Delta and returned to Hazlehurst in 1931 where he stayed for about a year. During that time he traveled throughout the Delta playing but used Hazlehurst as home. When Johnson returned to the Delta he is reported to have gained extraordinary proficiency, not only as guitarist, but singer as well. The Cross Road Blues has been used to perpetuate the myth of Johnson selling his soul to the Devil for his musical ability. The lyrics do not contain any references to Satan or a Faustian bargain, but they have been interpreted as a description of the singer’s fear of losing his soul to the Devil (presumably in exchange for his talent). Music historians believe that Johnson’s verses do not support the idea and many consider this interpretation a blight on the accomplishments of Robert Johnson. One has to only imagine that Johnson may have promoted the idea himself, and one could argue that “the ‘devil angle’ made for good marketing”.

While there are many crossroads in the Delta, the one most frequently identified with the origins of the blues is the intersection of Highways 49 and 61 in Clarksdale. In any event, it is clear that Clarksdale has fully embraced its history and today there are not only blues clubs, but the Mississippi Blues Museum.

Pluto

Richard Grant made the community of Pluto famous in his book, Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta and while there is not too much to see in terms of bright lights or shopping opportunities, it might make an interesting detour on a trip around the Mississippi Delta. The farm is about 43 miles SSE ATCF from Pluto.

Po’ Monkeys

I am saddened to report that the last of the rural juke joints in the Delta has met an untimely demise. For a five dollar cover charge, you could enjoy a bar that was a prime example of a cultural icon that flourished in the Mississippi delta over the last century. Unlike its predecessors, Po’ Monkeys rarely had live music but there was a DJ at least once a week. Inside, Monkeys, as it was called, was garish at best. The walls were decorated with old road signs, t-shirts, old posters, neon beer signs, and miles and miles of Christmas lights. Ask anyone in the area and they are likely to have a story about Po’ Monkeys.

It was run by Willie Seaberry, who by day worked for Park Hiter, the owner of the clapboard shack that was Po’ Monkeys and the farm on which it sat. However, Seaberry was the empresario of Monkeys. Seaberry lived in a room off the kitchen and was a constant fixture who greeted all comers. People from all over the world walked up the metal steps that led to the front door and came inside to experience a taste, if ever so fleeting, of what it may have been like in the jukes that were the venues where the Delta blues were born. Willie Seaberry was Po’ Monkeys until he died in 2016. Over the next year legal proceedings were required to settle Seaberry’s estate as he left no will. In November 2018 all the contents of Po’ Monkeys were moved into storage. Today, you will see a tenant house built nearly a hundred years ago, in its original location, no longer covered in the original signs and notices. The small fenced in area around a Mississippi Trail Blues Marker in front is littered with beer cans thrown on the ground and stuffed into the chain link fence. Monkeys looks the worse for wear these days, but there is still hope that this bit of Delta history can be preserved. Po’ Monkeys is located on Po’ Monkey Road, Merigold, 15 miles ATCF NNW from the farm.

Money, MS

Money is named for Hernando DeSoto Money, a politician who served both in the US Senate and House of Representatives from immediately after the Civil War until 1911. The Post Office in Money was established in 1901. In August 1955, Money became infamous as the site of the lynching of Emmett Till. Till, a 14-year-old African-American from Chicago, was visiting his uncle Moses Wright in Money. Till and his cousin went into Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market in scenic downtown Money, to buy candy. While in the store, Till was accused of whistling at Carolyn Bryant, the white co-owner the store.

Because of his familiar and suggestive interaction with Carolyn Bryant, her husband, Roy Bryant and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, abducted, tortured, and murdered Till. Till had violated a cardinal rule separating blacks and whites at that time. The “color line” was alive and well in Money. Bryant and Milam were arrested and tried for the murder, but were acquitted by an all-white jury. Several months later, they sold their story, and in an interview with William Bradford Huie published in the January 1956 issue of Look magazine, in which they confessed to the killing. In 2007 Carolyn Bryant revealed that she had fabricated details of the encounter in her testimony at trial.

Till’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, insisted on an open casket funeral for her son in Chicago. She wanted people to see that her son had been badly beaten before his death, and allowed news photographs of his body to be published. Money, Mississippi and Emmett Till are indelibly etched in civil rights history and the history of Mississippi. Money is approximately 25 miles ATCF due east of the farm.

The Burrus House

The Baby Doll House or Hollywood Plantation, also known as The Burrus House, is an antebellum plantation house in the Greek Revival style near Benoit, Mississippi started in 1858 and completed in 1861. Judge J. C. Burrus and his wife, the former Margaret Louisa McGehee, moved from Huntsville, AL to the Mississippi Delta in 1842, and settled on the frontier of newly-formed Bolivar County, near what is today Benoit, Mississippi. After a few years the Judge bought a large tract of land five miles from the Mississippi River, which would become known as Hollywood Plantation, because of the beautiful holly trees in abundance on the property. There they built a roomy log house to accommodate their growing family, and in 1858, the construction began on the plantation home and was completed in 1861.

Hollywood is the only antebellum “mansion-type” plantation house extant in Bolivar County. It survived the ravages of the Civil War for several reasons: General Peter Burwell Starke of the 28th Mississippi cavalry camped his men at Hollywood; it was located far enough from the river that it was out of range of Union artillery from the river; and a personal relationship dating from his law school days at the University of Virginia that Burrus had with the Union general who was in command Union forces in the area.

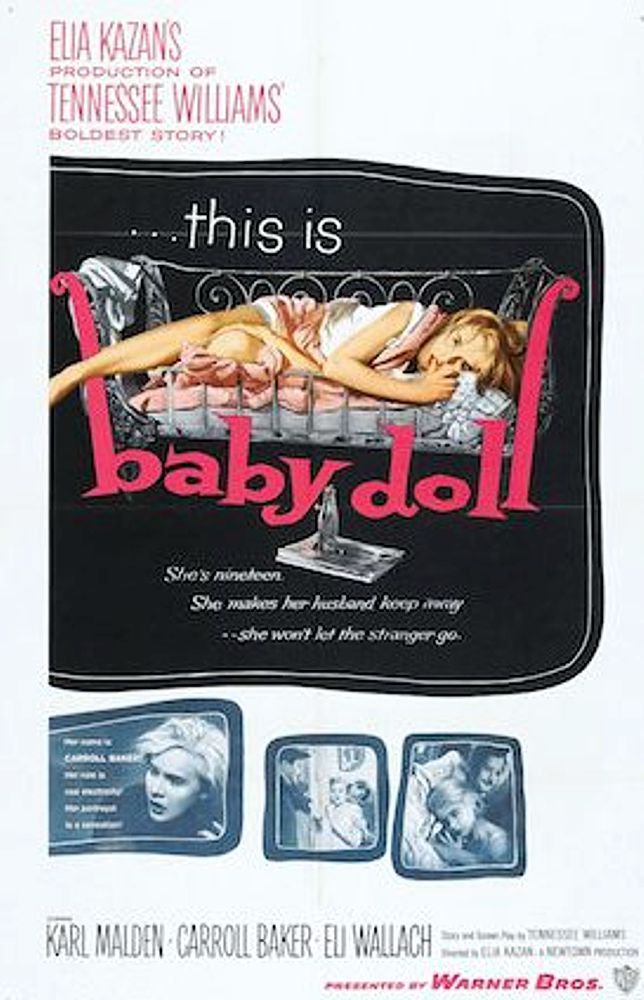

The home was occupied by the Burruses until around 1916, when J.C. Burrus Jr. moved out and took residence with his daughter, Maggie Burrus Barry. The house was then a host to different renters but subsequently fell into disrepair. In 1955 producer Elia Kazan and his co-producer Tennessee Williams began filming the movie Baby Doll at the house. Baby Doll is adapted by Williams from his own one-act play 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1955). The plot focuses on a feud between two rival cotton gin owners in rural Mississippi; after one of the men commits arson against the other’s gin, the owner retaliates by attempting to seduce the arsonist’s 19-year-old virgin bride with the hopes of receiving an admission by her of her husband’s guilt.

The Hollywood Plantation and the Baby Doll house are near Benoit, Mississippi approximately 20 miles ACTF due west from the farm.

Mound Bayou

Mound Bayou, Mississippi is a town in Bolivar County, Mississippi, and is notable for having been founded as an independent black community in 1887 by former slaves led by Isaiah Montgomery. The wilderness in northwest Mississippi was a relatively undeveloped frontier, and blacks had a chance to make money by clearing land and use the profits to buy lands in such frontier areas. By 1900 two-thirds of the owners of land in the bottomlands around Mound Bayou were black farmers. With the loss of political power due to state disenfranchisement, high debt and continuing agricultural difficulties, most lost their land and by 1920 most were landless sharecroppers. As cotton prices fell, the town suffered a severe economic decline in the 1920s and 1930s. Mound Bayou was further ravaged by fire in 1942 but was revived by the construction of the Taborian Hospital and the singular efforts of its chief surgeon Dr. T.R.M. Howard, who eventually became one of the wealthiest black men in the state. Howard owned a plantation of more than 1,000 acres, and a construction firm in addition to his medical practice. In addition, Howard was active in the early civil rights movement.

Mound Bayou was also the home to Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer, among other notable civil rights activists. At its height, the city was home to credit unions, insurance companies, a hospital, five newspapers, and a variety of businesses owned, operated, and patronized by black residents. Mound Bayou is a crowning achievement in the struggle for self-determination and economic empowerment. Mound Bayou is 17 miles ATCF from the farm,

We Can Always Hope