Covid and Life in the Delta

While I grew up in a small town in Mississippi I had little hands-on experience with farming. About as close to farming as I experienced in my early life was picking tomatoes, squash, and butter beans in my grandfather’s garden, trying my hand (literally and figuratively) at milking a cow, as well shelling beans and peas on lazy summer afternoons sitting under a giant pecan tree. It goes without comment that I did not come equipped with the job skills that made me an instant farming wizard.

As a child I had the opportunity to visit the Mississippi Delta on many occasions with my parents in the early 1950s. In my view as a young child, the Delta was an amazing place. I remember the excitement I felt when told that we were going to the Delta for the weekend. My father and mother had friends who lived on a farm just outside Greenville, Mississippi. I am not sure how large the farm was, but it seemed to me that it stretched from horizon to horizon with endlessly long rows of cotton. I remember that in addition to the owners, a number of people who worked on the farm, lived there as well. In particular, I realize now that as a child there were social injustices being played out in front of my eyes, but as a child all I could see was the wonderful opportunity to play with kids my own age. Mind you these playmates were not the children of the couple with whom my parents and I were visiting, but the children of delightful black man who ran their house. According to my memory, he was a giant. A tall, lanky black man that had a gentle manner and a deep voice that I can only describe as like velvet. I am sure that my parents enjoyed these visits a great deal, but to me they were truly magical.

One of my fondest memories happened on an exceedingly hot and humid afternoon, something that is not uncommon in this part of the world in July. For a kid, the best way to cool off was to find some water and do everything possible to enjoy it to the utmost. On this particular afternoon, all the little kids and I reveled in a galvanized #3 washtub sitting in the shade of their house filled with water. Further research has revealed the washtub that seemed immense to me at the time was only about 2 feet in diameter and held about 17 gallons of water. No matter the size or the capacity, the washtub it was the center of our games. Running around it, jumping in it, splashing water from it on my playmates was extraordinary. Little did I know then the profound effect that these experiences would have on me in later life.

These early visits to the Delta gave way to friendships with a number of my college classmates that lived throughout the Delta. Coming here always was and continues to be a source of anticipation as I leave the hill country, cross the Yazoo River and enter the flat expanse of the Delta. Today as much as ever, when I cross the Yazoo River bridge on my way from Jackson to the farm, I feel a kind of relief as I look out over the expanse of farmland and Highway 49 turns gently northeast I know I am headed home.

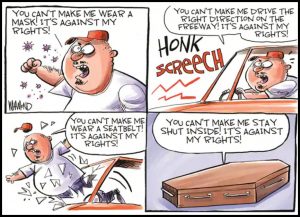

It is mid March 2021 and the world is in the midst of a global pandemic. Covid-19 is a potentially lethal virus that has spread around the world, infecting almost 120 million of people and killing almost 2.4 million worldwide. Mississippi is no different, and while the number of cases and deaths are not as large as more populous areas of the country, the fatalities are just as tragic. Turn on television and we are bombarded by sophisticated graphics offering visual documentation of the horrible death and suffering this tiny organism is inflicting upon us. In addition, we are admonished to do everything we can to stop the spread of this disease – wear masks, enforce social distance, wash hands, get tested, etc. Yet as I write this, the governor of Mississippi has lifted the mandate on wearing masks in public. Of course, the vaccines are becoming available and more and more people are doing the responsible thing and getting vaccinated. The politics of mask wearing has stolen the show from the obviously more important public health messages. Now people who had simply not followed any public health guidelines will be able to say I told you so, and go blissfully about their business.

These observations have led me to think about what Covid-19 has revealed about our society, and in particular about my fellow citizens in the Mississippi Delta. It is no secret that Mississippi is a poor, under educated, disease-prone state, that is at the bottom of almost every ranking of socio-economic and health indicators published. What I see around me is a microcosm of the class system. Disdain for masks is simply an indicator that many of my fellow Mississippians are deeply distrustful of any edicts from and agency of the Federal government, as well as the those from any Washington politician who think they know what’s best for people in my part of the world. It seems to me that we need to understand why people in my part of the world have such great distrust for government and the so-called coastal upper class elites. Better than upper-class, the term overclass more accurately depicts what I see around me. There is an overclass that exists in all spheres of life, and it is populated largely by urban, college-educated professionals, often with postgraduate degrees. Roughly one third of Americans have a bachelor’s degree, and slightly more than 10% have a master’s degree or more. In Mississippi these numbers are 23.1% and 8% respectively. These are the people that make up the overclass.

Many of the people around me have an abiding distrust of the overclass for good reason. They see the ruling class enacting laws and economic policies that while presented as good for the entire country, largely benefit the members of the overclass. People in my world see large-multinational companies dictating economic and social policy that does little to improve their lives, and in many cases hurts them. When politicians and “talking heads” on television proclaim the inevitability of globalization and technological change and the need to accept it, they resist. This more cosmopolitan view of the world has not permeated rural Mississippi for good reason.

People around me do stuff. They do stuff with their hands. They do stuff outside. They are brick masons, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, not to mention farmers. Now consider for a moment how covid-19 has affected them. Many are self-employed. The work that they do has dried up. For those lucky enough to have work, the future is uncertain at best. The message that the country should stay on lockdown or be reopened with great caution because of the public health consequences of viral transmission simply makes no sense if you are unemployed. For people concerned about not having money for food, rent, and the necessities of life, the public health argument is a difficult one to swallow. Moreover, the people making the argument on television, in the government, and medical types, all have jobs and a regular paycheck. Other members of the overclass have jobs that allow them to work from home and

follow the behavioral proscriptions to minimize viral transmission. This is roughly one-third of the US workforce. But for the other two-thirds workers who build stuff, cook french fries, clean hospital rooms, drive tractors, and have jobs that are not based directly on their Internet connectivity, the luxury of working from home is simply impossible. It should come as no surprise that among those affected most by covid-19 there is a deep skepticism about any pronouncement by experts?

follow the behavioral proscriptions to minimize viral transmission. This is roughly one-third of the US workforce. But for the other two-thirds workers who build stuff, cook french fries, clean hospital rooms, drive tractors, and have jobs that are not based directly on their Internet connectivity, the luxury of working from home is simply impossible. It should come as no surprise that among those affected most by covid-19 there is a deep skepticism about any pronouncement by experts?

Anthony S. Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has said he understands that maintaining these guidelines is “inconvenient.” Inconvenient does not begin to describe the reality among the working class in America. Platitudes and of feigned understanding have done little to engender the attitude and belief that there is anything but a rigidly enforced class system in the US, that cares little about the day to day existence of those who work with their hands.

It seems to me that as we emerge from this pandemic with the increased availability of vaccines, it is important for all of us to listen much more carefully to the concerns not only of the public health experts, but of working Americans as well. Everyone has an opinion about what the country should do, but it is clear to me that we must recognize the diversity of opinion, and not write off parts of the population just because we see differences, rather than similarities. I am proud of my home state and the people of the Delta, while recognizing both the strengths and weaknesses of this place I call home.

The people who live in the Delta are a hardy, self-sufficient lot. They appreciate hard work and have pride in what they do. While the results of failed state and Federal assistance programs are evident everywhere, there remains a certain quiet dignity and independence that is clear to all willing to take a careful look.